Finally, OSCP!

03 Jun 2018My last few months were full of adrenaline, insomnia and fun, provided by the Offsec team (creators and maintainers of the Kali Linux distro) and their PWK course. There are many reviews of the course (my favorites being this one and this other one), and it looks like it’s my turn to add to this informal tradition of writing yet another “I’m an OSCP!” blog post.

The course

The course is comprised of two parts: a PDF with accompanying videos showing the tools of the trade, and a lab full of targets to hack. The written/video material is very good, and shows the most well-known tools a pentester should be acquainted with, plus a few tricks here and there (I particularly enjoyed the discussion on uploading files with Windows built-ins).

These materials are just an appetizer for the main dish: Offsec provides a network of machines with different configurations that mirror real-life situations a pentester might find during an engagement. Each machine is unique and requires a different strategy for breaking in and escalating privileges. The game aspects of the course (“yay, popped another box!”) are addictive and ensure the student will learn good pentesting habits through repetition.

Some boxes are standard installations of known/vulnerable software, some are more CTF-ish, which keeps things interesting. Something that sets this course apart from other challenges like Vulnhub or Hackthebox is the presence of multiple networks and dependencies between machines, requiring a good job of post-exploitation on the student’s part.

Those who have been in the labs know how frustrating, difficult and ultimately rewarding the course is.

Reporting, Emacs style

The exam (about which I cannot talk too much, due to course rules) demands a written report of the steps taken to break into the machines, much like a professional engagement. In addition, the student gets extra points in the exam if s/he delivers a test report for the boxes popped during the labs. This is the “unsexy” part of the job, but I figured I could make it a little more interesting…

Among the tools suggested in the course is KeepNote, a note-taking application used to store everything: commands, shells’ screenshots, you name it. Since Emacs already has Org-mode, I thought, why not just use it? It turned out better than expected.

This blog post by Howard Abrams explains in much better detail all the built-in functions Emacs has for literate programming in Org-mode. Since a pentest report falls into this broad category, I decided to give it a go for the labs and got hooked - it really makes everything much easier.

The highlights for me were:

Named sessions

From the Org-mode documentation:

For some languages, such as python, R, ruby and shell, it is possible to run an interactive session as an "inferior process" within Emacs.

This means that an environment is created containing data objects that persist between different source code blocks.

Babel supports evaluation of code within such sessions with the :session header argument.

This functionality allows you to write commands much like you would in a script, keeping all state across executions! Much like iPython and other “scientific computing” platforms, it serves as a literate REPL, allowing you to keep notes on all computations of interest.

This is all driven by standard Elisp code, and, in the case of the shell wrapper (what you’ll be working with most of the time when pentesting), Emacs’ built-in subshell. This means you get some cool stuff for free:

- History enabled by default (via M-p / M-n), which is particularly useful for shells with no tty

- Easy to copy/paste content because it’s just text in an Emacs buffer. In particular, you can even save the whole terminal interaction as just another file.

The :session keyword allows multiple interactive shells, making it easier to juggle a bunch of different commands to get a remote shell (e.g. you set up a netcat listener in a victim-sh session, and run an RCE exploit in a exploit-victim session).

Exporting

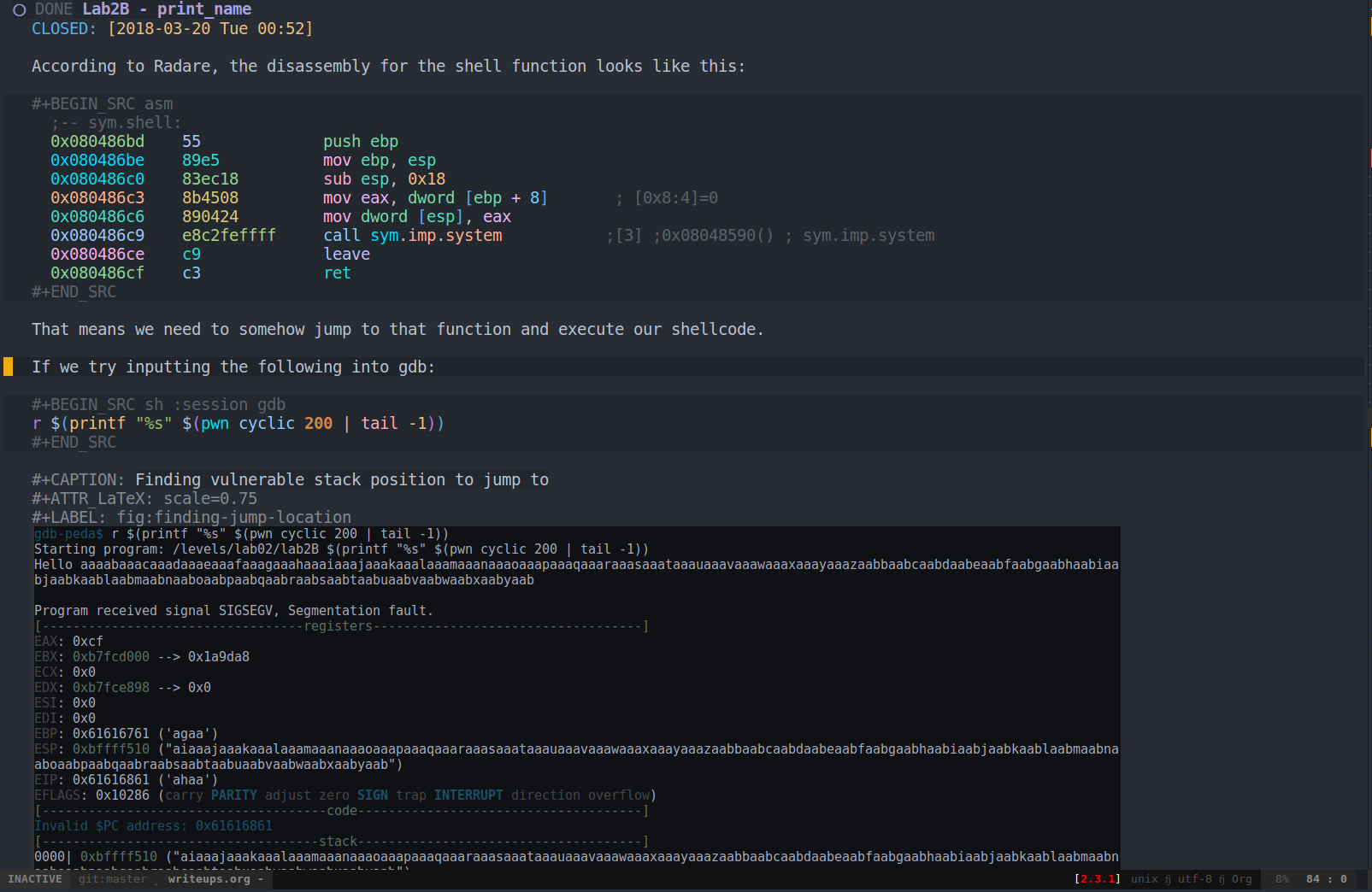

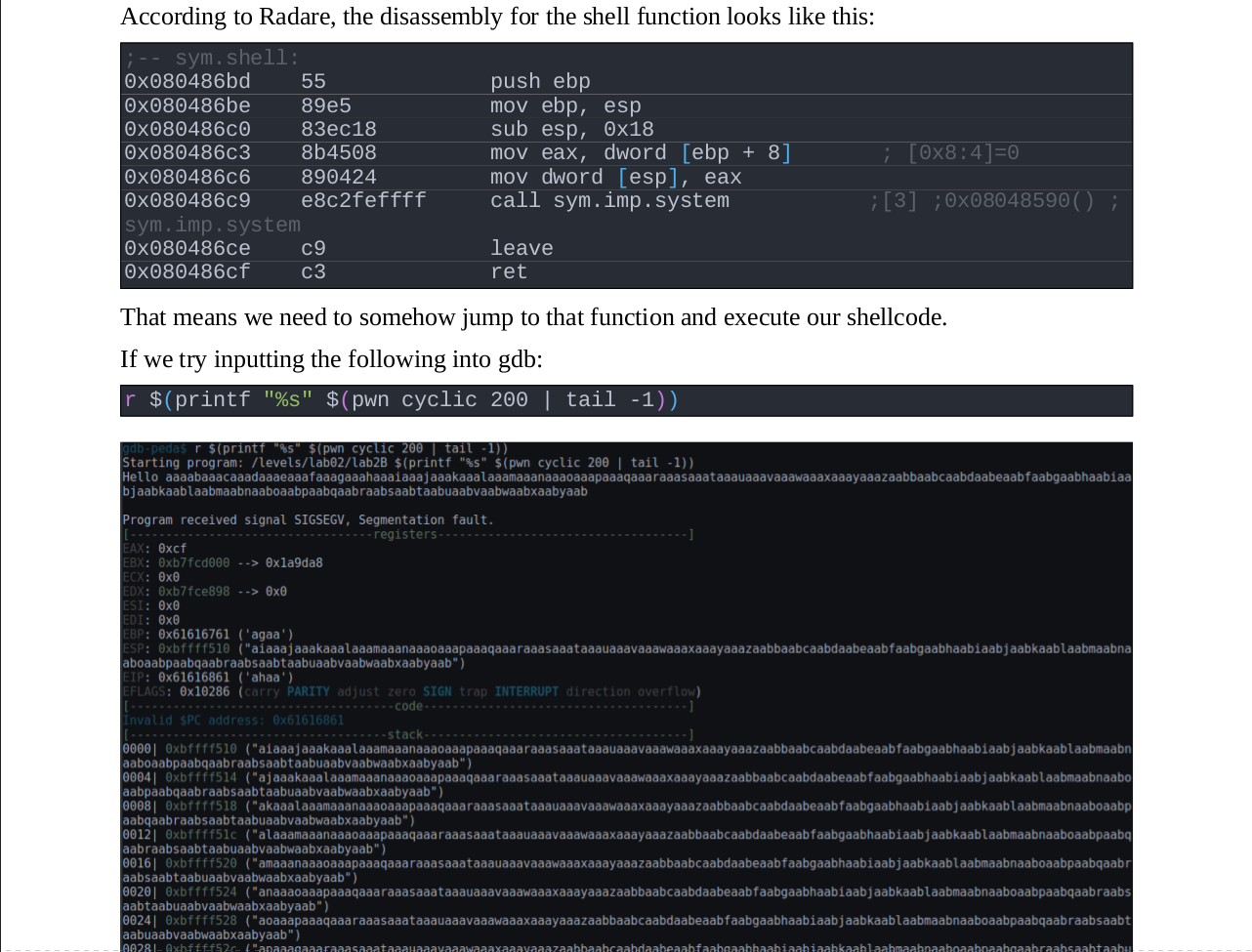

This is an example source Org-mode document (taken from my notes on the MBE exercises):

Org-mode allows one to easily export a document to multiple formats. It’s as easy as C-c C-e $FORMAT.

After exporting to ODT/PDF, this is what it looks like:

This made it very easy to convert my notes into a quality document. Since the commands were already there, with some comments in place to remind me what they did, the only work necessary was to tidy up the notes and export. No fiddling with converters/formatting necessary - all handled by Org-mode.

Did I mention it’s also possible to “tangle” the commands together into standalone scripts if necessary, so you have a way to distribute this in a more fitting form to non-Emacs users?

Why?

All this looks like a lot of work. And it is. Why should you bother going through all this, if it’s not going to directly impact your day job?

As a software developer, it’s easy to overlook security. We all have days when we think “this is a clumsy hack, but it’ll have no further repercussions, and we’ll fix it later”. This sort of rationale goes out the window when you know how an attacker is able to use that particular issue to pwn your app and turn your servers into Monero mining bots. Or, even worse, your customers’ machines.

It also shows how security failures tend to be systemic. Most machines in the course are designed not to fall to a point-and-click exploit, but to a combination of weak credentials, too-much-exposed services and lax access controls. Gives one a new appreciation for the work of devops/sysadmin people, keeping everything patched and running smoothly.

Besides, the labs are very fun, and I definitely recommend going for it if you’re looking for a challenge.